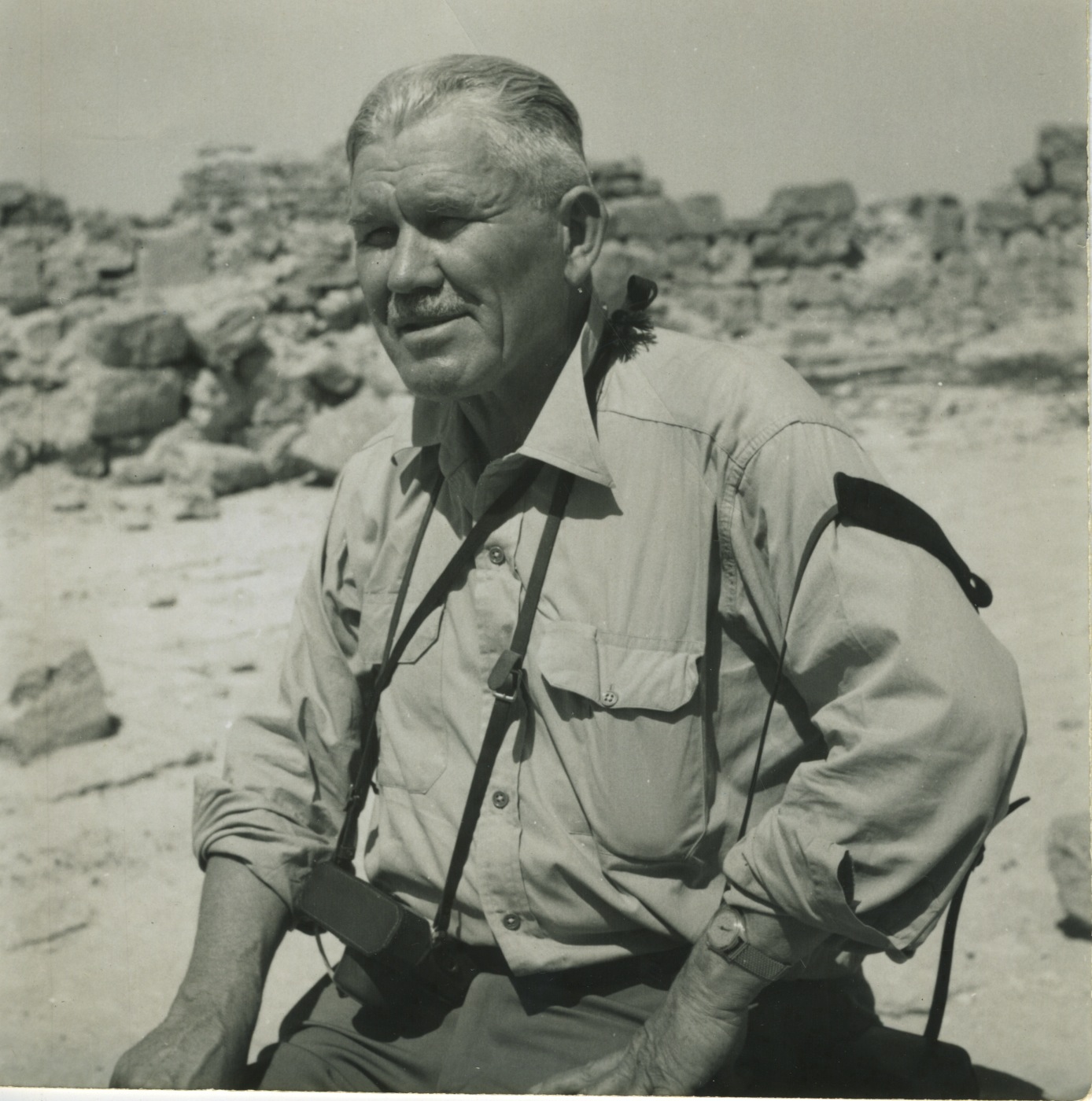

“Our relations to the earth are more than economic; they are moral. We are custodians of the bountiful land, its waters, its plant and animal life, its hidden riches, and perhaps most important of all, its soils….” – Walter Clay Lowdermilk (1888-1974)

“Our relations to the earth are more than economic; they are moral. We are custodians of the bountiful land, its waters, its plant and animal life, its hidden riches, and perhaps most important of all, its soils….” – Walter Clay Lowdermilk (1888-1974)

“We don’t need powdered milk; we need Lowdermilk.” – Mordechai Bentov, Israeli Minister of Development (1955-1961)

Before Israel became a nation, before drip irrigation and before desert agriculture became commonplace, one American soil scientist drove 30,000 miles across a collapsing world to answer a deceptively simple question: were these lands ruined by climate—or by human neglect?

The answer mattered to America. By the late 1930s the question was no abstraction. The Dust Bowl had blackened the American sky. Rome’s former granaries lay eroded. North Africa’s terraces had collapsed into dust. If food was the currency of nations, he liked to say, soil was the capital. Without that capital North Africa and the Levant were bankrupt.

To find out, Walter Clay Lowdermilk set out to examine the regions that had once fed empires—the Levant, where agriculture began, and North Africa, Rome’s breadbasket. In the shadow of a Second World War, he loaded his wife, Inez; their two children, Billy and Winnifred; his niece Elizabeth; his secretary Cleveland McKnight; and eventually even an incontinent puppy named Maktub (It is written) into a 1938 Buick. Over nearly two years they visited 3 continents, 17 countries, 124 sites, and traveled more than 30,000 miles.

The others might be looking for interesting scenery. He, the Assistant Chief of the Soil Conservation Service was interested in proof.

At fifty, Lowdermilk kept a schedule that exhausted men half his age, leaving at dawn and returning long after dark.

He may be the most influential man you have never heard of—unless you are Israeli.

While surveying British-controlled Palestine under the League of Nations Mandate, found Palestine to be like much of what he had seen in North Africa, “A sad commentary on man’s stewardship of the earth.” The only bright spots were the kibbutzim staffed by Jewish Zionists, most of whom had never farmed before their arrivals. Green oases blossomed in and around each kibbutz, which were often placed on the poorest of soils.

After Palestine, the Lowdermilks worked among the cedars above Beirut writing reports for H.H. Bennett, chief of the Soil Conservation Service. There, Inez read a newspaper report: a small, aging “one-funnel” Greek freighter carrying 655 Czechoslovakian Jews had sent an SOS. Fleeing Hitler, the refugees had been denied entry to Palestine. The ship was towed into Beirut so it could be cleared of vermin.

Inez went to the harbor.

Later she wrote of what she saw: 160 people crammed into each hold, stacked six tiers high on wooden shelves lined with straw. No light. No stairways. Toilets installed only after pleading. Water hauled up by bucket for washing or flushing. For eleven weeks they had drifted in summer heat. Many had developed scurvy.

These refugees were trying to reach the homeland promised in the Balfour Declaration. British authorities, wary of Arab unrest and dependent on Middle Eastern oil, refused to let them land. Palestine had been roiled by revolt since 1936. London would not risk further upheaval. The British were not the only government denying entry to Jews fleeing Hitler. That June the United States government had denied entry to the 937 Jewish refugees aboard the passenger ship MS St. Louis. The ship returned to Europe. Tragically, 254 of these were eventually murdered in the Holocaust.

Inez brought Walter to the docks.

“What is happening to the Jewish people is terrible,” she told him. “It is long past due for Christians to give the Jews a new deal.” When they returned to America, she said, she would tell anyone who would listen what Hitler was doing—and how Britain was locking the doors of the Jews’ ancestral home.

The encounter changed him. For years Lowdermilk had studied soil erosion. Now he saw another kind of erosion: erosion of humanity. Here were people barred from soil they believed was theirs. If soil could determine the fate of civilizations, it might also determine the fate of a nation not yet born.

Both Inez and Walter Lowdermilk belonged to a generation that believed prosperity could be scientifically engineered. Born in 1888, he grew up in an America intoxicated with reform and scientific optimism. Darwin had redrawn the map of life; just as Adam Smith had redrawn the map of society. Many believed the future could be managed, improved—even perfected. Lowdermilk absorbed that faith early.[1] At one point, young Walter wondered how he can become a great man. Inez Marks would later provide the answer.

After serving in the First World War with the Army’s Lumberjack Regiment, he joined the young U.S. Forest Service in Missoula, Montana. In 1922, while building a reputation as a research officer, he proposed to Inez Marks, a missionary home on furlough from Sichuan. She agreed—on one condition: he would return to China with her. She told him he could help end famine there. It was, her father quipped, “a marriage made in Heaven—because there wasn’t enough time for it to happen on earth.”

In Nanjing, Lowdermilk taught forestry as part of the China International Famine Relief Commission’s effort to make relief “scientific.” The river carried the pulverized remains of hillsides tilled bare.

When he traced the silt to its source, he found gullies carved into loess as soft as flour. Crops grew on exposed slopes. Trees clung only to temple groves. The contrast was unmistakable. Where forests stood, soil held. Where trees fell, land bled into rivers.

There he formed the conviction that would define his life: soil mismanaged is civilization undone. “[U]nless the farmer is prosperous, no one is prosperous,” he would say.

He and Inez might have stayed in China for the rest of their lives except the experiment ended abruptly on March 20, 1927, during the Nanjing Incident. Revolutionary troops entered the city shouting, “Kill the foreign devils.” A man beside Lowdermilk was shot and killed; a rifle was raised toward him. He escaped with his life.

The lesson was indelible. Political instability, hunger, and land mismanagement were intertwined.

The Lowdermilks returned to America penniless and shaken. Back in California, Lowdermilk resumed his work. At the University of California’s Forest Experiment Station he earned a doctorate and began pioneering research in soil conservation. His work drew the attention of Rexford Tugwell, Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, who recruited him to Washington to help establish what became the Soil Erosion Service under Hugh Bennett.

By the late 1930s, the Dust Bowl had demonstrated that even modern nations could exhaust their land. Someone proposed a comprehensive survey of territories once ruled by Rome—regions that had flourished agriculturally before sliding into decline. Lowdermilk seized the opportunity. If food was the currency of nations, he liked to say, soil was the capital. To squander it was a crime against both humanity and nature.

On August 10, 1938, the Lowdermilks boarded the S.S. Manhattan and began their three continent odyssey. They examined abandoned terraces, ruined aqueducts, overgrazed hillsides, and river valleys stripped of topsoil. They also saw signs of renewal—proof that disciplined stewardship could restore damaged landscapes.

When they returned home, Walter and Inez secluded themselves for six months in their basement and wrote with urgency. The result, published in 1942 as Palestine, Land of Promise, electrified Zionists worldwide. It challenged the British claim that the country could not absorb more immigrants. Lowdermilk argued that through coordinated water management, erosion control, and regional planning—what he called a Jordan Valley Authority, modeled on the Tennessee Valley Authority—Palestine could sustain millions more people.

The future of a homeland, he insisted, would be decided in watersheds.

Lowdermilk believed that restored soil would yield more than crops. Protect the land, manage the water, prevent famine—and allow people to live in harmony with nature and with one another. The land, he was certain, could be redeemed by science and stewardship.

Whether human conflict could be redeemed as well was another matter.

History would test that faith in ways he did not foresee.

One thought on “He may be the most influential man you have never heard of—unless you are Israeli.”