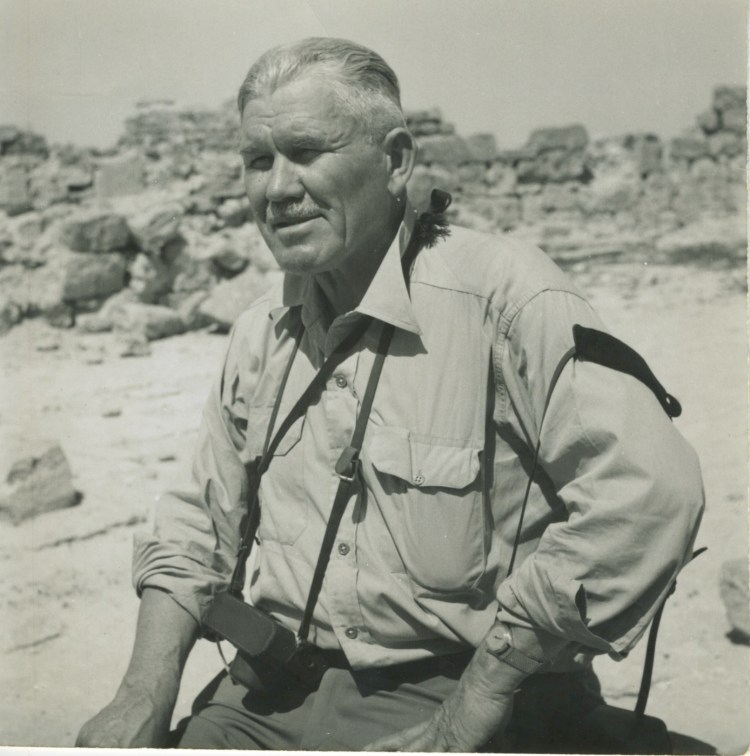

Walter Lowdermilk was recruited by Rexford Tugwell in 1933 to serve as the second-in-command of the new Soil Erosion Service, later called the Soil Conservation Service. In 1938, he was tasked with studying how soil affects human life and well-being. He spent two years exploring lands once ruled by the Romans to find answers. This is his report on what he discovered in Italy.

—

Since ancient times the people of Italy, from one generation to another, have had to snatch the soil from the fury of destructive floods rushing off the precipitous mountains, or rain eroding cultivated hillsides by unbelievable labor in terracing, or from marshes infested with malaria.

The struggle against the marshes and malaria dates back to ancient times. It is known that Appius Claudius, at the end of the Fourth Century B.C. was one of the first to attempt reclamation of these marsh lands through which runs the famous Appian Way to Rome. Then Julius Caesar, Augustus, Trajan, Theodorio, and later on a number of Popes, particularly Pope Pius the Sixth, all had set their hands to the task but without success.

In spite of all the land reclamation efforts of the centuries the present Government of Italy found itself confronted with barren, marshy, depopulated districts scattered here and there in almost every region of Italy. The forty-three million inhabitants of Italy had occupied all available lands. They had terraced steep hills and mountains for cultivation. Their towns and cities were precariously perched on the steep cliffs, or tucked away in the deep folds of interior mountain ranges. From these lands an average of 353 people per square mile, as against 50 per square mile in the United States, must secure food and sustenance from the soil. The only available areas suitable for colonization were the barren wastes of the marsh lands and the large estates of rich land owners (sic) which were largely used for grazing.

With the unification of Italy, reclamation was felt to be a national problem, and from 1870 on, various laws were passed which proved insufficient for the problem. It remained for the “Mussolini law” of December, 1928, to coordinate all phases of reclamation, and initiate a tremendous effort for the complete recovery of all lands of Italy for the sake of a better economic, hygienic and social future for the nation. During these past ten years, under the stimulus of the Fascist regime, successful reclamation and colonization of barren and marsh lands has surpassed that accomplished through all preceeding (sic) centuries.

The Fascist Regime maintains that land should belong to the people and be occupied in such a manner as to provide food and occupation for the greatest number; and has devoted its greatest energies and efforts to reclamation and colonization. It recognizes that rural society is a reservoir of strength without which the cities would decline by fossilizing, growing old, and losing their population. It emphasizes that maintenance and fertility of soils is all Important; for the production of essential foods is a pillar in the economic structure of the nation, which must not be allowed to fall.

This policy of making lands available for the people was initiated at the close of the World War when the King of Italy transferred the Crown Lands to a National Association of Ex-Service men, and when the Government voted funds to the amount of sixty million dollars for the reclamation of lands to be occupied by ex-soldiers and their families.

The reclamation of the Pontine Marshes and notable other areas are the work of this Association. Private land owners are urged to work in cooperation with the Government in the reclamation and colonization of lands which are deemed best for the welfare of the nation. However, if land owners refuse to cooperate, their lands are expropriated. With a definite policy and suitable laws for its execution, Tas-cist Italy has accomplished some magnificent examples of reclamation of waste lands. She has thus provided new homes and lands for her peoples, and created an entirely new Province out of the former ill-famed, fever infested Pontine Marshes.

It is said that the remains of sixteen cities, all pre-dating Roman occupation, were found in these Pontine Marshes, proving that this malaria infested, uninhabitable area once sustained a numerous population. The geologic processes which transformed the area are evident. The soils on the plains are largely derived from volcanic ash. The mountains also were doubtless equally covered with this material at the time of eruptions. Volcanic ash erodes and washes rapidly when stripped of vegetation. The precipitous mountains, rising abruptly from the Pontine plains, are now gleaming white as snow, showing the now bare surfaces of limestone rock.

It is very probable that, with the rapid rise in population after the founding of Rome in the 8th Century B.C induced the clearing of that vegetation on these mountains for cultivation or by grazing of herds. The steep gradients, combined with heavy rainfall, would permit rapid erosion of the volcanic ash soils from the slopes. This mass of material filled up drainage channels and silt was carried out to the sea, where the erosional debris was sorted. The waves piled up the sands in dunes along the shore; this ridge of shore dunes served as a dyke against the drainage of the area. Each rainy season impounded its mountain flood waters against this barrier of dunes. Undrained pockets, and the fifteen thousand acres slightly below sea level, formed marshy lakes; only small islands of higher lands remained for grazing. These belonged largely to the great landed estates. Land use was very primitive in form and was used chiefly for pasture. The occasional laborers, recruited from the neighboring mountains, were killed off or driven away for months at a time, by the deadly forms of malarial fevers infesting the swamps. The little city of Ninfa, the Pompeii of the Middle Ages, reveals its walls, its forsaken squares covered with flowers and wild plants – its population was completely annihilated or driven out by the deadly mosquito.

Mussolini’s speech at the inauguration of the new Province of Littoria[1], created from the newly populated Pontine Marshes, is significant of the spirit in which the problem was attacked:

“Only three years ago, there stretched around us the deadly marshes. We have waged a very hard battle. We had to face nature, material difficulties, and the skepticism and moral cowardice of those who doubted the victory. For us Fascists, the fight itself is more important than the victory, because when a battle is begun with an iron will, it is unfailingly crowned with success”. All the precautions and preparations for a major battle were coordinated in this attack to reclaim the Pontine Marshes, and destroy the deadly enemy entrenched there. Machinery and all necessary equipment were assembled in a camp outside the battle zone.

Instead of venturing slowly, with small groups of workers, into the domains of the enemy, thirty thousand men were assembled. The housing quarters for this army had been built in sections, with each door and window well screened. When all was in readiness a day was set to advance, and night found the workers well within enemy territory, housed in insect proof dwellings. Each building wasin charg e of an officer to whom all inmates daily reported before work, and in the officer’s presence, each swallowed the large portion of quinine allotted him. Work was feverishly rapid, but ceased entirely before sun-down so that the men were all in barracks, behind screens, before the deadly winged messengers flew out in search of their evening meals. There were several varieties, the most vicious of which caused death within a few hours. With the first symptoms, patients were rushed from the marshes to hospitals behind the lines.

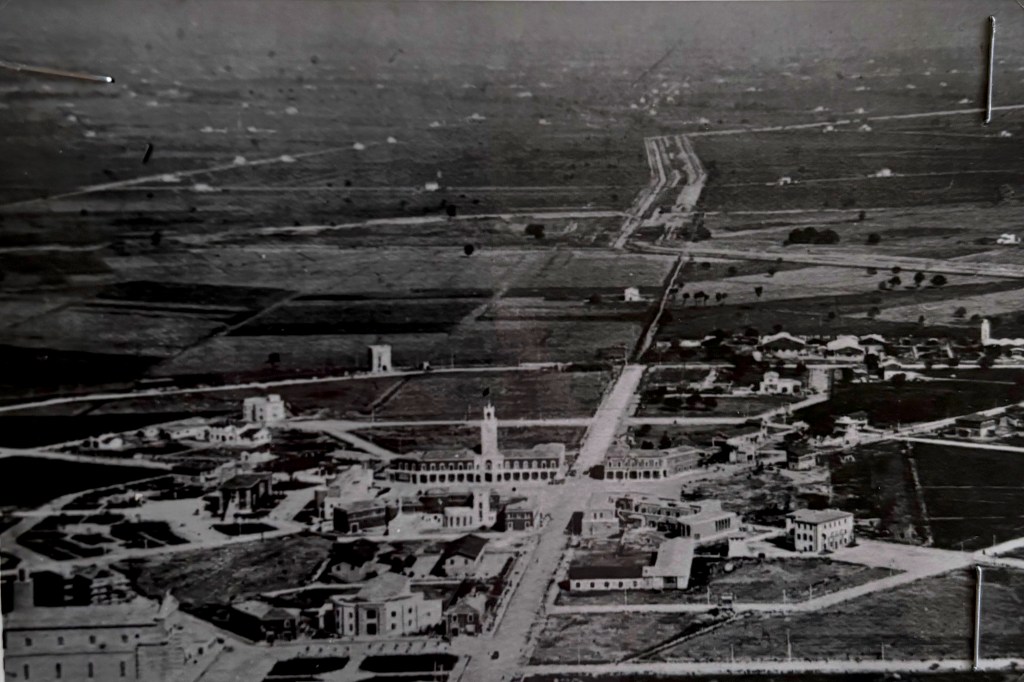

The rapidity with which this campaign progressed is amazing. The first work began in November 1931 with the clearing of about six hundred acres of swamp forests, which mere converted into charcoal, two months later, drainage was sufficiently complete for the construction of the reinforced concrete farm houses on the first area. In June work was begun on the new city of Littoria and in December, six months later, all public building, and housing sufficient for eight thousand persons, had been completed.

Littoria, as well as each of the other new towns on the reclaimed marsh lands, is a model city, selected from competitive architectural designs; with parks and wide streets providing ample parking space for future autoists. The ultra-modern dwellings and apartment houses are built of reinforced concrete, painted on the outside. The city Hall is magnificent with its marble stairs and Council Chambers, carved furniture, and floors pared with red and black marble. The misery of the past is recalled by a huge and appealing painting in the reception hall; the father has been stricken in the field with fever and is dying; the children are weeping while the mother, with uplifted arms, looks Imploringly heavenward with an unforgettable expression of hopelessness and sorrow; in the background is the small farm house and beyond it, the marsh lands. The poverty and tragedy is a striking contrast to the hygienic, permanent cities which have sprung so suddenly from the former deadly marshes.

With the completion of the Littoria section, work was pressed forward, and within two and one-half years the the (sic) one hundred and eighty-two thousand acres of Pontine Marshes had been reclaimed, and became the nucleus of this new Province of Italy. Although in number it is the 93rd Province, settlement was so immediate that it ranks 79th in population and 61st for density, Since this reclamation work had been largely accomplished by the National Ex-Service Men’s Association, in cooperation with the neighboring communes and land owners, the new area was settled chiefly by ex-service men and their families, from densely populated areas around Venetia.

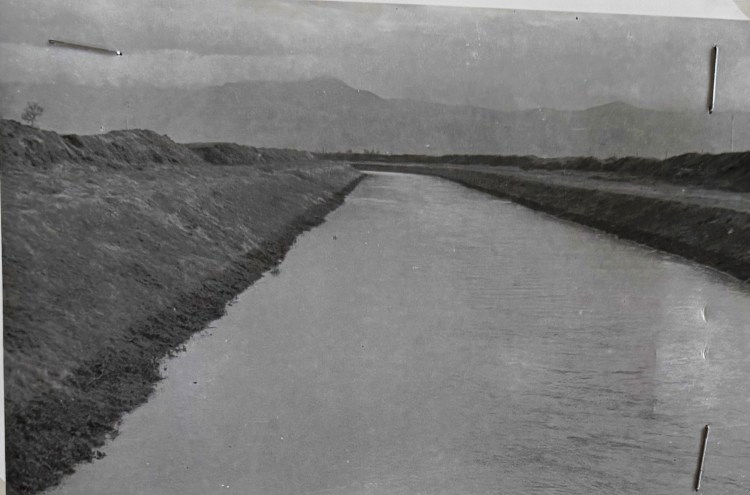

To reclaim the first one hundred and four thousand acres, it was necessary to build two hundred and sixty miles of roads, move five million seven hundred fifty-nine thousand two hundred and fifty cubic yards of soil and build one thousand and ninety-seven miles of canals. The huge Mussolini Canal and several smaller ones, skirt the lower slope of the precipitous mountains and carry all mountain flood waters direly across the plains to the ocean. Waters are collected by fifteen pumping stations run by power from the mountains twenty-five miles away. There had Just been a heavy rain, and when we visited Mazzocchio,the largest of the stations, draining twenty thousand acres, four of the seven pumps were working, lifting two thousand six hundred twenty-five gallons per second twelve to fifteen feet to the higher canals which carry waters out to the sea. Floating grass mowers are constantly on duty, cutting the water vegetation to keep canals open and prevent infestation by mosquitoes.

It is an interesting landscape of concrete tile roofed farm houses, painted cream, light blue, tan, orange or white – stretching to distant horizons. The colors vary according to the time each section was completed, and whether ownership of land belongs to the National Ex-Service Men’s Association, or to the communes that formerly held grazing rights in the marshes. The houses are outwardly attractive, of Mediterranean architectural design. Each home contains three bedrooms, storeroom and kitchen, which is the family meeting place, and serves as living room for entertaining guests. An arched porch, under one of the bedrooms, provides a delightful workshop or protection from the sun. Tach home is supplied with a good well, about twenty feet deep, and an outside oven for the baking of bread. For some reason these are not in connection with the house, but some yards away. American women would resent the necessity of walking in rain or hot sun to bake and watch the bread, which is the chief article of diet here. Each home is equipped with a shed for fifty or sixty chickens and a family pig or two. The average number in these farm families is said to be ten or eleven. There are usually four or five children, two parents, a grandparent or two, and frequently a married son and his family. Thus some households may run as high as sixteen.

There is a model community city, similar to but smaller than Llttoria, for every two hundred farms. Here are located schools, churches, stores, a theater, civic buildings, and gas stations – all built in harmonious architectural designs, from public funds of the same corporation or association which reclaims the land. Children from these two hundred farms either walk or ride bicycles on the well built highways to their school center. Education is free through primary grades. This is considered sufficient except for the exceptional farm child.

It is indeed a remarkable and astonishing achievement. Seven years prior to our visit, this area was composed of deadly marshes, impassable to man and beast alike; the water buffalo alone was able to survive. We drove for an entire day, over fine roads, seeing thousands of permanent concrete farm houses, and visiting model towns of distinctive architecture. Pumping stations and the vast network of canals, at various levels, were being tested by the recent heavy rains, and all were working efficiently. It commands admiration for the rapid, successful accomplishment of a task which had defied the engineering knowledge of centuries past.

The Government body which directs and controls the entire program of reclamation and colonization, is the under-Secretaryship for Integral Land Reclamation, and is dependent on the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. The Undersecretary is aided by a group of executive and consultative bodies.

The Italian Fascist method is to setup in every area to be reclaimed, one or more corporations of owners. Their task is the maintenance and expedition of reclamation work. These are composed of representatives of the Government, representatives of private land owners in the area to be reclaimed, and corporation officials. There are in existence in Italy, about seventeen hundred corporations and trusts or juristic persons, that control a total of about forty-two million five hundred thousand acres. The most powerful corporation is the National Association of Ex-Service men, which, under the president of the council, has the power to purchase tracts of land, and where necessary, use compulsion to force private land owners to sell or cooperate with the reclamation scheme. The areas to be reclaimed, whether marshes or large estates of private land owners, are taken over by the corporation and prepared for intensive agriculture, and divided into small holdings for individual farm families.

During the past fourteen years, the Fascist Regime, through the medium of these corporations, has carried out, more or less completed, work on twelve million seven hundred sixty-seven thousand three hundred forty-two acres, of which five million, five hundred fourteen thousand acres are almost or entirely completed. This is more than five times the amount of reclamation accomplished during the fifty-two years from 1870 to 1922.

As to expenditure during this period approximately three hundred sixty-three million dollars have been spent on public works of which about two hundred seventy million dollars belong to the Fascist Era. An additional amount of approximately one hundred twenty-four million dollars has been granted for improvements to private landed properties. Thus more than one-third the total expenditure has been made to assist private land owners in the development or colonization of their lands.

The Fascist Regime believes in the fundamental importance for the nation’s welfare, of private ownership of land, but makes the transformation of estates for colonization compulsory, and insists on the cooperation of small land owners in an area to be reclaimed. The private owner may transform his estate for colonization at his om expense if he wishes, or he may borrow money from the state and then sell a portion of the lands for repayment – or he may receive assistance from the State. If he refuses, his lands may be expropriated. Considerations of private loss or gain are not taken into account in determining the advisability of the work. A private owner may not wish to invest his capitol(sic) in the transforming of his estate from pasture into agricultural lands for intensive cultivation.

The nation, on the other hand, in its unity and continuity, will be rewarded for the immediate financial sacrifice by the increase in wealth for the whole nation – and the private citizen has the advantage of belonging to a stronger social order. While private owners must comply with certain responsibilities such as the upkeep of minor roads and the preparation of the land for cultivation – drainage, main roads and certain other features are designated as public works and are paid for by the state.

When nearing Rome, we were astonished to see vast uninhabited areas, being newly broken up into farms, and planted to grain. There were dozens of plows at work, drawn by six or eight gray oxen with long horns more terrifying in appearance than the old-time long horns of the Texas range. It was found that these lands had belonged for centuries to a huge estate, used for grazing, which the new regime had forced open for cultivation and colonization.

The agrarian schemes to be initiated on the reclaimed territories, were found to be best carried out by peasant families who have long been associated with a special type of work, and have their own interest in the production.

Fascist Italy, has and is, setting her national lands in order for permanent agricultural production and has placed tens of thousands of her people on newly reclaimed lands. The development of such large regions of agricultural lands, and new cities to serve them, created demands for so much labor that the unemployed who have been put to work reclaiming these areas have been absorbed into permanent positions. These works have served a three-fold purpose – they provided immediate employment for tens of thousands of unemployed during the years of depression – provided agricultural lands and homes for overflowing populations – and created an inestimable wealth for the nation as a whole.

W. C. Lowdermilk

The ill-famed fever-infested Pontine Marshes which defied reclamation for more than 2,000 years and which covered more than 181,000 acres have been reclaimed as fertile and productive farms with five small cities to serve them. Before reclamation, it was so impossible to survey these marshes that three men went together on horseback so as to rescue each other when floundering. Some of the lands were 15 feet below sea level and dunes along the coast prevented drainage of higher lands.

The large well-built Mussolini canal carries the rain waters which rush off the denuded mountains direct to the ocean, across the Pontine area, some of which is below sea level. December 1938. W.C.L.

The local rain waters are collected at fourteen pumping stations which raise the water to a sufficient level for it to flow out to the sea by its own power. The farm houses are all built of reinforced concrete, built to last a thousand years. December 1938. W.C.L.

Littoria under construction. From a land of desolation and disease, Pontine marshes were transformed within a period of two and a half years to a vast fertile farming area with more than 4,000 reinforced concrete houses located on farms and five towns to serve them with schools and churches and all public buildings. Littoria, the largest town, was completed within six months from the time the cornerstone was laid. All towns laid out with distinctive types of architecture.

[1] Now called Latina, the province was named after Littoria, the capital city founded by Benito Mussolini on June 30, 1932, as part of a major fascist-era reclamation project. The name “Littoria” derived from the fascio littorio, a symbol of the Italian Fascist Party and it is a call back to ancient Rome. Roman fasces is a bundle of rods tied around an axe, symbolizing authority, unity, and power. -NB

Lowdermilk admired Il Duce’s leadership and positive attitude. He mentioned to Malca Chall in the California Oral History Project, “This was a chance to make something beneficial for my country.” Many progressives viewed fascism as a modern and bold approach to governance that involved strong government action and national progress, aligning with their goals of social reform and planning. This was not an outlier opinion many found this ideology intriguing. Even Will Rogers, the popular humorist, remarked, “I’m pretty high on that bird,” and endorsed dictatorship if led by the “right dictator.” Government action, that is force at the end of a gun, for the people’s benefit, like land renewal, is necessary—what could be more important than protecting the earth for humanity?